Glucose management generally focuses on what we eat. However, when we eat is now recognized to be significant as well. With around-the-clock accessibility of highly palatable foods (i.e., processed and refined products, pop), excessive exposure to artificial blue-light from

screens, and increased demands to squeeze as much as possible into the 24-hour day, we have weakened our connection to nature and disrupted our internal clock. ‘The lack of alignment with the circadian clock has been reported to influence food intake, glucose metabolism, weight regulation and obesity’ (Henry et al., 2020). This is important to consider given that diabetes mellitus continues to be a leading chronic disease worldwide and dietary interventions remain a cornerstone in diabetes prevention and management.

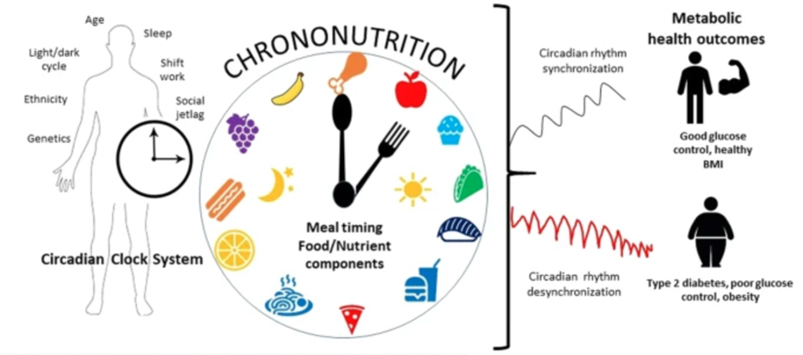

Beyond calories and macronutrient breakdown, the field of chrononutrition looks at the relationship between circadian rhythms and food intake and how meal timing affects metabolism (Adafer et al., 2020). Eating patterns have shifted with the majority of calories being consumed later in the evening. This sets the stage for metabolic dysfunction since the hormones involved in glucose metabolism, such as insulin produced by the pancreas, typically peak during day-light hours. A cohort study investigating the relationship between late-night-dinner and glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes found that consuming dinner after 8pm is a risk factor for poor glycemic control (Sakai, 2018).

Figure: Chrononutrition plays a role in regulating circadian rhythms that influence metabolic health and risk of diabetes mellitus (Henry et al., 2020).

Time-restricted eating (TRE) focuses on the time during which food is consumed, usually within a 4-12 hour period, resulting in a state of fasting over a 12-20 hour period. Within the eating window, individuals are to eat without any restriction on the quality or quantity of food intake, however reduced caloric consumption by 20% on average is observed, without an alteration of macronutrient distribution (Adafer et al., 2020). Based on the systematic review of TRE on human health, benefits include:

- Weight loss (specifically reduction in body fat)

- Decreased fasting glucose and insulin resistance

- Reduced cardiovascular risk (triglycerides, total cholesterol, systolic and diastolic blood pressure)

- Improved sleep quality and quantity

- Increased energy, alertness, and focus

TRE is a simple and cost-effective lifestyle practice to harness your circadian rhythm so you can align with your hormones, optimize metabolic health, and improve glucose management. Check out Satchin Panda’s myCircadianClock for feedback on your eating, sleeping, and activity patterns and remember…

- First morning sunlight exposure. Light/dark cues are important to maintain the relationship between circadian systems and energy homeostasis (Oike et al., 2014).

- Time-restricted eating. Consuming meals within an 8 to 10-hour eating window supports metabolic health and blood sugar regulation.

- Minimize blue light at night. Blue light exposure can impact the production of melatonin, our sleep hormone, contributing to sleep disturbances and increased oxidative stress.

- Avoid eating 2-3 hours before bedtime. This promotes initiation and maintenance of sleep and fasting overnight which is associated with lower systemic inflammation reducing the risk of metabolic diseases.

References:

Adafer R et al. Food Timing, Circadian Rhythm and Chrononutrition: A Systematic Review of Time-Restricted Eating’s Effects on Human Health. Nutrients. 2020 Dec; 12(12): 3770.

Henry, C.J., Kaur, B. & Quek, R.Y.C. Chrononutrition in the management of diabetes. Nutr. Diabetes 10, 6 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-020-0109-6

Oike, H., Oishi, K. & Kobori, M. Nutrients, Clock Genes, and Chrononutrition. Curr Nutr Rep 3, 204–212 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-014-0082-6

Sakai, R. et al. Late-night-dinner is associated with poor glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes: The KAMOGAWA-DM cohort study. Endocr. J. 65, 395–402 (2018).

647 551 2898

647 551 2898